What Wood Wants: Correspondence With Shuji Nakagawa

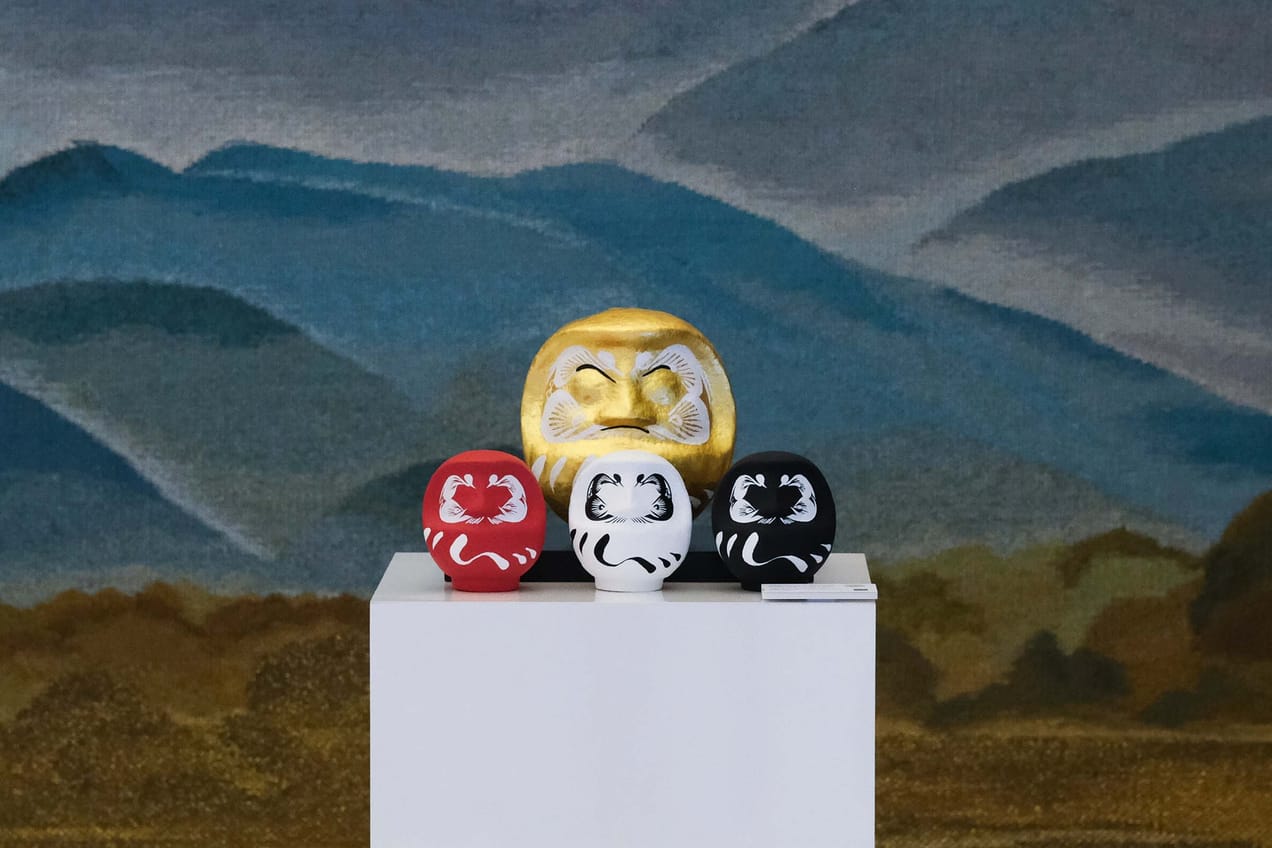

A week before my experience Kaida sensei, I found myself in another workshop in Shiga prefecture, this time starting not with carefully selected bamboo but with a mallet, a wedge and a massive tree trunk. I was visiting Shuji Nakagawa's studio - an accomplished artisan known for his wooden buckets (ki-oke) and iconic collaborations like the Konoha champagne cooler for Dom Pérignon.

I first met Nakagawa-san in 2013. In person, he projects the aura of a no-nonsense shokunin more comfortable at the workshop than in front of an audience. But since the pandemic, I've noticed a transformation. Back then he started hosting online discussions called 'Tree Talk on Thursday', inviting woodworkers, designers, and connoisseurs to talk about craft. When the world reopened, he began engaging not just through what he creates but through words too, a philosopher-guide alongside his making practice.

That crisp autumn morning, I joined a group of knowledge workers as part of Professor Eugene Choi's research programme at Doshisha Business School, investigating how to translate tacit knowledge for non-craftspeople.

The goal of the day was to understand wood better - where it comes from, how it's processed - and, above all, to learn to listen to it. Nakagawa-san gave us wood and tools to split, saw, cut, plane and sand. To think with our hands and senses, not just our heads.

Shuji Nakagawa's workshop in Shiga. Photos by Gianfranco Chicco

Thinking Through Making

Anthropologist Tim Ingold challenges the Western separation between mind and hand, thinking and doing. In the conventional view, knowledge comes from standing outside what we wish to understand. But when you think through making, knowledge grows from the inside - through sustained involvement with materials and tools. "The maker is someone who has to follow the material, has to join his or her own life to the lives of the materials that they work with," Ingold says.

He calls this conversation with materials correspondence, learning to notice and respond to subtle variations in grain, texture, resistance. The skilled maker must balance two speeds: the imagination leaping forwards and the slow, patient work of the hands, keeping their "eyes trained on the far horizon while still engaged in the labours of proximity."

Videos by Gala Espel and Professor Eugene Choi

This matters beyond the workshop, where information floods us but knowledge remains scarce. For Ingold, art includes craft, and he argues: “We really need art to challenge the foundations of technoscience, that is to reawaken our senses and to allow knowledge, once again, to grow from the inside, so that it becomes part of who we are and part of how we relate to the world around us.” When we learn to work in correspondence with materials, we develop a better relationship with the world, one rooted in attention and sensory engagement rather than detached analysis.

"It sometimes seems that the more knowledgeable we are, the less attention we pay to what is going on around us in our environment.” - Tim Ingold

In the workshop. Photos by Gianfranco Chicco

Making The Familiar In A New Way

At the start, Nakagawa-san gave us a quick demonstration on how to make a small wooden box. However, he encouraged us to play with the wood and the tools with no specific goal but paying attention to what was happening. Only once we 'find' something in the material should we start working on it.

So what did I find at Nakagawa’s workshop? Something both familiar and unexpected. While slicing a chunk of wood I noticed that its fibrous nature was forming a thin edge on one side and a curve towards the end of the other one. That curve felt just like that of the chashaku I had been making at home.

I decided then to follow that form and create a dual-purpose instrument: from one side, a scoop for matcha; from the other, a kashikiri, the small dessert knives used in the Japanese tea ceremony to cut and eat the sweets that accompany the matcha. I made four of them, plus a rest to present them.

The final result, a dual chashaku-kashikiri. Photos by Gianfranco Chicco

When we were done, we did a show-and-tell session for everybody to share the results of their efforts. This made me realise that I had been so immersed in my own work that I hadn’t paid much attention to what was happening around me. Some of my fellow participants created smooth or quirky sculptures, boxes of different sizes, kitchen utensils, hanging mobiles and much more.

I'd come to understand wood but learned to listen instead. Through improvisation, I found something familiar expressed in a new form. Creativity, Ingold reminds us, lives not in novelty but in the improvisatory process itself.

Notes

- 'Tree Talk on Thursday' is a play on words given that Thursday (木曜日) in Japanese includes the ideogram for wood (木).

- The Tim Ingold quotes in this article are taken from his talk 'Thinking Through Making'. For further reading, I recommend his book 'Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture'.

Like the content of The Craftsman? Share it with a friend! You can support my work by offering me a virtual coffee ☕️

つづく