Mountain Eel: Making Chashaku with Kaida Sensei

When I confirmed my return to Kyoto, I took it as an opportunity to progress in my chashaku-making. My friend Toshiyuki Matsubayashi from the Asahiyaki kiln recommended we visit Mai Miyake's studio in the mountains of Shiga to study under Kaida sensei. When someone from a 400-year pottery lineage says there's a master he wants to learn from, you pay attention.

Kyokko Kaida has the energy and playfulness of a Studio Ghibli character. He started studying the way of tea in the 1960s and as a self-taught chashaku maker in 1980.

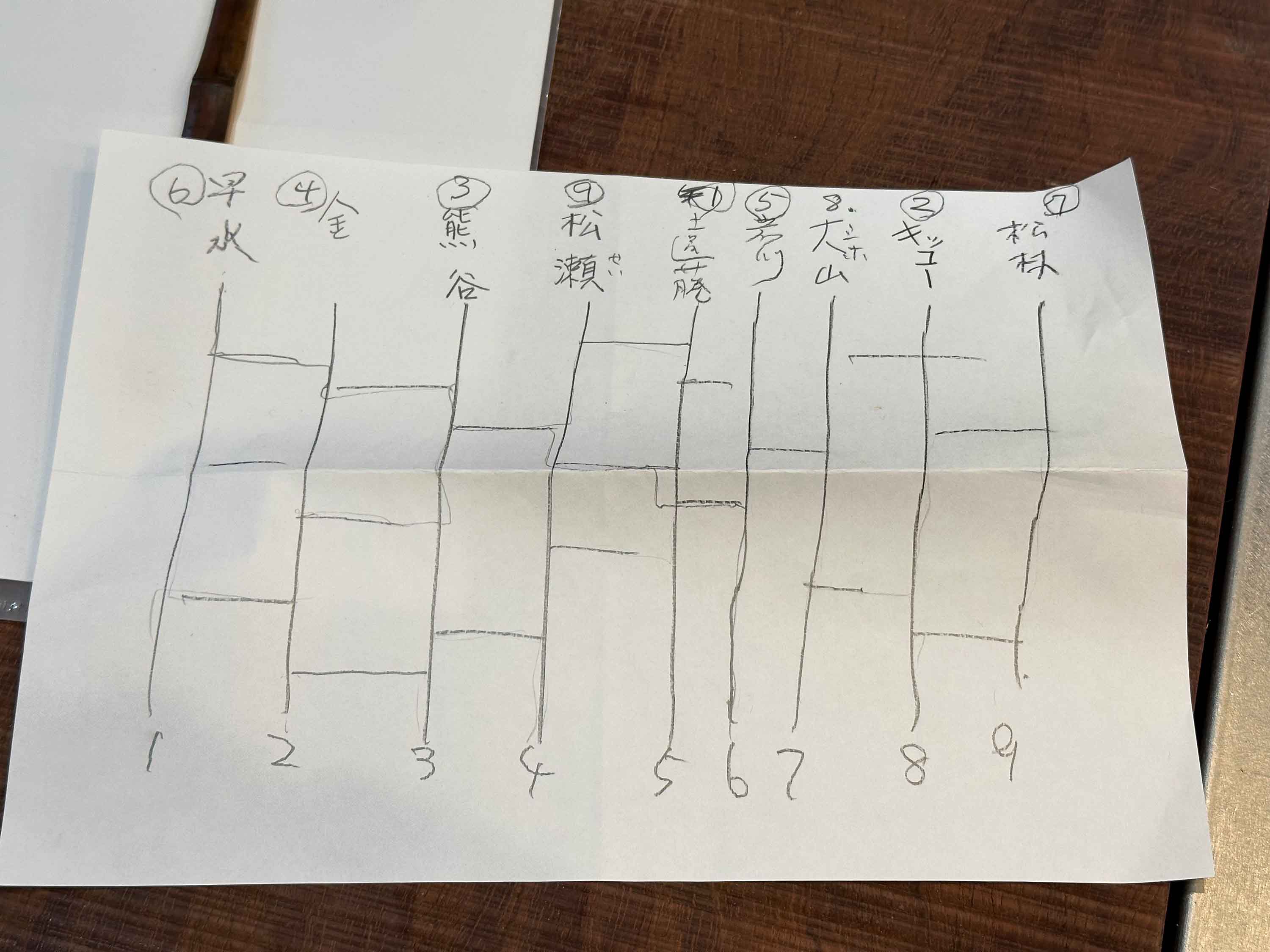

First we had to choose blanks from a selection of susudake, bamboo salvaged from old thatched houses coloured by decades (if not centuries) of exposure to soot from the open hearth, staining it from silky caramel to deep black. No two were alike, and as old homes disappear so does this type of bamboo. To allow for a fair selection for each of the nine participants in the workshop, Kaida sensei ran a fun Amidakuji lottery, a paper-and-pen method used to guarantee random pairings.

Selecting blanks fairly with the Amikuji lottery (centre). Photos by Gianfranco Chicco

When it comes to susudake, the weirder, the better. Until now I had only used standard bamboo from a DIY store. Working with an irregular, precious material forces you to see what's already there, which features to keep, accentuate, or let go.

We had a few photocopied pages with guidelines and measurements but I barely used them during the day. Kaida sensei’s teaching consisted of minimal verbal instruction; we learned by watching and doing. However, he was paying close attention to how our hands moved, and available for questions, which he answered by demonstrating directly on our pieces.

Kaida sensei's hands-on teaching. Photo by Gianfranco Chicco

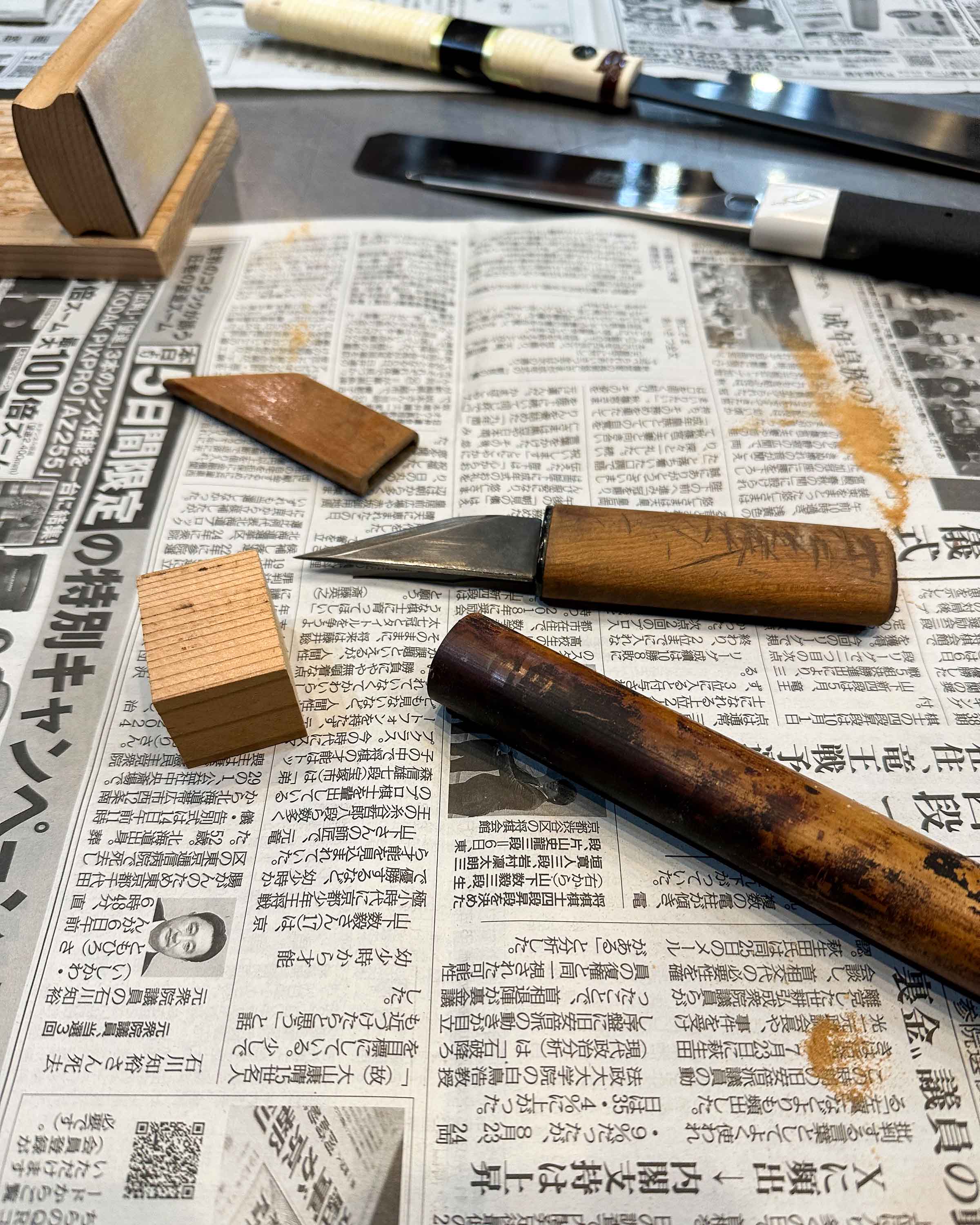

Unlike my solitary practice at home, being with a group at a communal table allowed me to see how others interpreted their material. Shared tools favoured trying different types of kiridashi, saws and Kaida sensei's homemade tools. There was no chit-chat, rather a silent show-and-tell.

Making a chashaku requires dozens of decisions that make each one unique: node placement, handle thickness, smoothness, curvature, tip style, balance in the hand and on top of a tea caddy. It’s believed the final result captures some aspect of the maker’s personality, and this is particularly cherished by chajin, tea people.

Making in group allows you to learn from others too. Photos left by Toshiyuki Matsubayashi, photo right by Gianfranco Chicco

It’s also important to know when to stop before that fatal extra stroke that could ruin it all, something I struggled with before. Under Kaida sensei’s skilled observation I learnt restraint and the art of finishing.

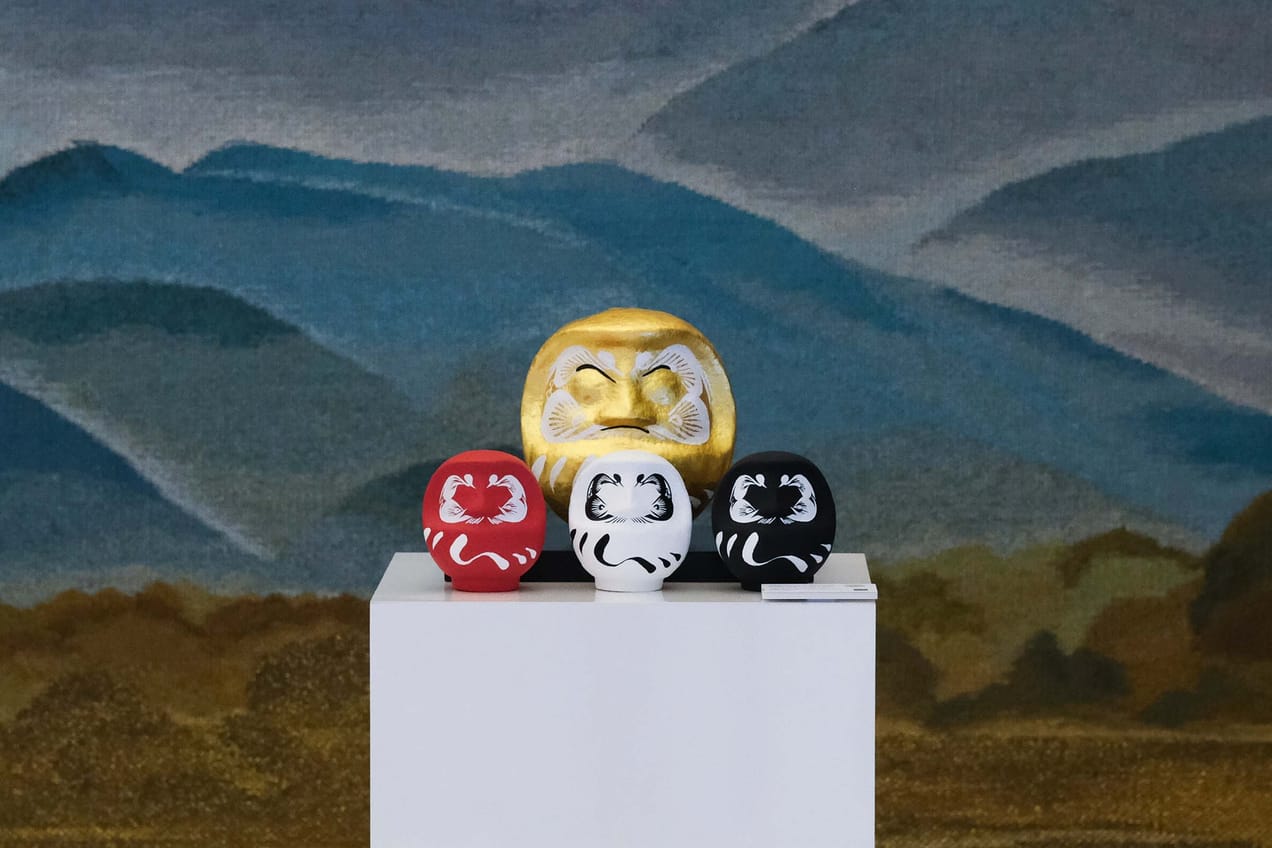

Afterwards, we moved onto the tatami tea room, where he prepared tea for each one of us using our individual chashaku, commenting on how they felt in the hand and allowing the group to admire each other's creations.

Putting our chashaku in action in the tea room. Photos by Gianfranco Chicco

Back at the workshop to make the tsutsu (the protective tube, my first), we chose bamboo to match the style and colours of the scoop and carved a cherry wood cap with the kiridashi. We had to decide which side would be the front and cut it flat to write the chashaku’s poetic name with brush and ink.

Making the tsutsu. Photos by Gianfranco Chicco

I named mine 'Mountain Eel'. The susudake's smoky tones, rugged texture and slender shape reminded me of grilled unagi, which we had eaten for lunch earlier that day at Kaneyo, a restaurant founded in 1872. Some names choose themselves.

Presenting the final results and the glorious lunch at Kaneyo, featuring dashi-maki tamago on top of grilled unagi. Photo centre by Toshiyuki Matsubayashi, others by Gianfranco Chicco

Like the content of The Craftsman? Share it with a friend! You can support my work by offering me a virtual coffee ☕️

つづく