The Serendipity Engine

Earlier this year I left my job. I felt a strong urge to recharge physically and, more important, mentally. The role had created a series of positive connections and had me embark on an intense public speaking spree, but I was exhausted and creatively stuck. On top of that I wanted to stop doing certain things (like chasing people), and start doing others.

In the note I sent out to my friends and network I mentioned that I’d be undertaking a Serendipity Break, which wasn’t a nice way to announce that I wasn’t going to work for a few months but that I wanted to actively explore different possible paths.

The concept of taking a serendipity break is based on my belief that luck doesn’t exist and that new, unexpected opportunities can be the result of feeding the Serendipity Engine.The Oxford English Dictionary defines serendipity as “the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way”. The term was coined in the 1700s and inspired by the Persian fable of The Three Princes of Serendip, where said princes made discoveries via a mix of unplanned accidents and chance.

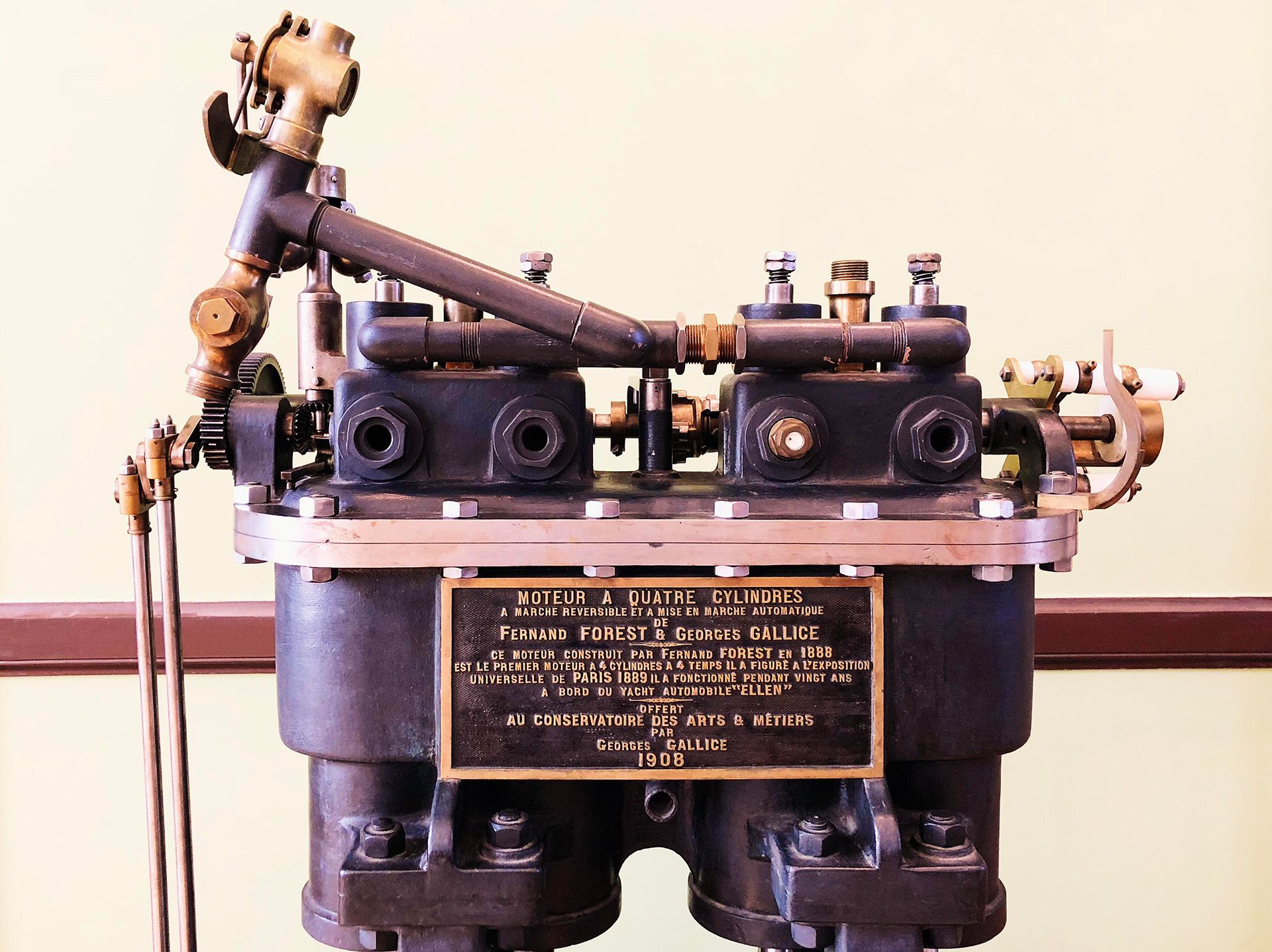

The Serendipity Engine works just like an internal combustion engine and, like with a high performance muscle car, you need to feed it with the right kind of propellant. In this analogy, the fuel is made of different activities, skills, and conversations. In my case, I select them so that they are deliberately out of, or tangential to, my current professional domain. The engine also requires maintenance and fine-tuning via iterations and changes to any activities or skills I become involved with.

Catering for my Serendipity Engine is not exactly a strategy, but a way to discover doors that I didn’t know even existed. If it sounds like something out of a Neil Gaiman story or akin to Douglas Adams’s Infinite Improbability Drive, it’s because I’ve always been fascinated by the unexpected, often absurd worlds both actors created.

Renowned designer Stefan Sagmeister started his personal tradition of taking a sabbatical every seven years because, despite all the success achieved with his work, he “was bored. The work became repetitive”, and he found that in the long run his creative output benefited from those off-work explorations.

Author Steven Johnson uses the concept of the adjacent possible to describe how different elements and ideas can be combined in various ways to create new elements and ideas, which expand the adjacent possible itself, allowing even more new creations to emerge in a virtuous circle of sorts. The Serendipity Engine operates in a similar way, adding new stimuli into my life, and alllowing new and unexpected things to emerge.

“The strange and beautiful truth about the adjacent possible is that its boundaries grow as you explore those boundaries.” - Steven Johnson, Where Good Ideas Come From

In his book The Craftsman, the sociologist Richard Sennett describes how “skill builds by moving irregularly, and sometimes by taking detours”, which is akin to keeping the Serendipity Engine in perpetual motion to encourage the strengthening of current skills and allowing the development of new ones.

During my current serendipity break I’m feeding the engine with: research for a book project that has been in the back-burner for about a year (and is not related to my previous job); curating a summit in Copenhagen about endings in life, work, and relationships; learning new skills like pottery, painting with watercolours, dancing Salsa, and taking writing courses on Masterclass; eclectic reading, both for the book project but also following other oft-neglected interests; going to events, conferences, and exhibitions (like the Fuorisalone in Milan) as well as visiting London’s vast museum offerings; traveling to a handful of cities I’ve always wanted to visit; hanging out with friends and acquaintances I haven’t seen in a while; being open to meeting up with strangers via intros or just random encounters while doing all of the above; slowing down and renewing the commitment to a series of personal rituals.

On a final note, when I started my degree in industrial engineering back in the mid-90s, we were required to attend an assessment session with the university’s psychologist. (I can’t really remember why we had to do it, but it was compulsory for all freshmen). At a certain point she asked me about my hobbies and interests, and upon hearing my reply, observed, with a concerned tone, that I had too many of them and that that was not a good thing.

Well, I can’t say whether it’s a good thing or not, but in the 24 years since that meeting, I have become who I am professionally by following my curiosity.