Slow prosperity: empathy and (small) business

On April 14th 2023 I hosted an online session called “Slow prosperity: Empathy and Business” with 6th generation Japanese master craftsman Takahiro Yagi of Kaikado. Kaikado has been making tea caddies - 茶筒, chazutsu - since 1875.

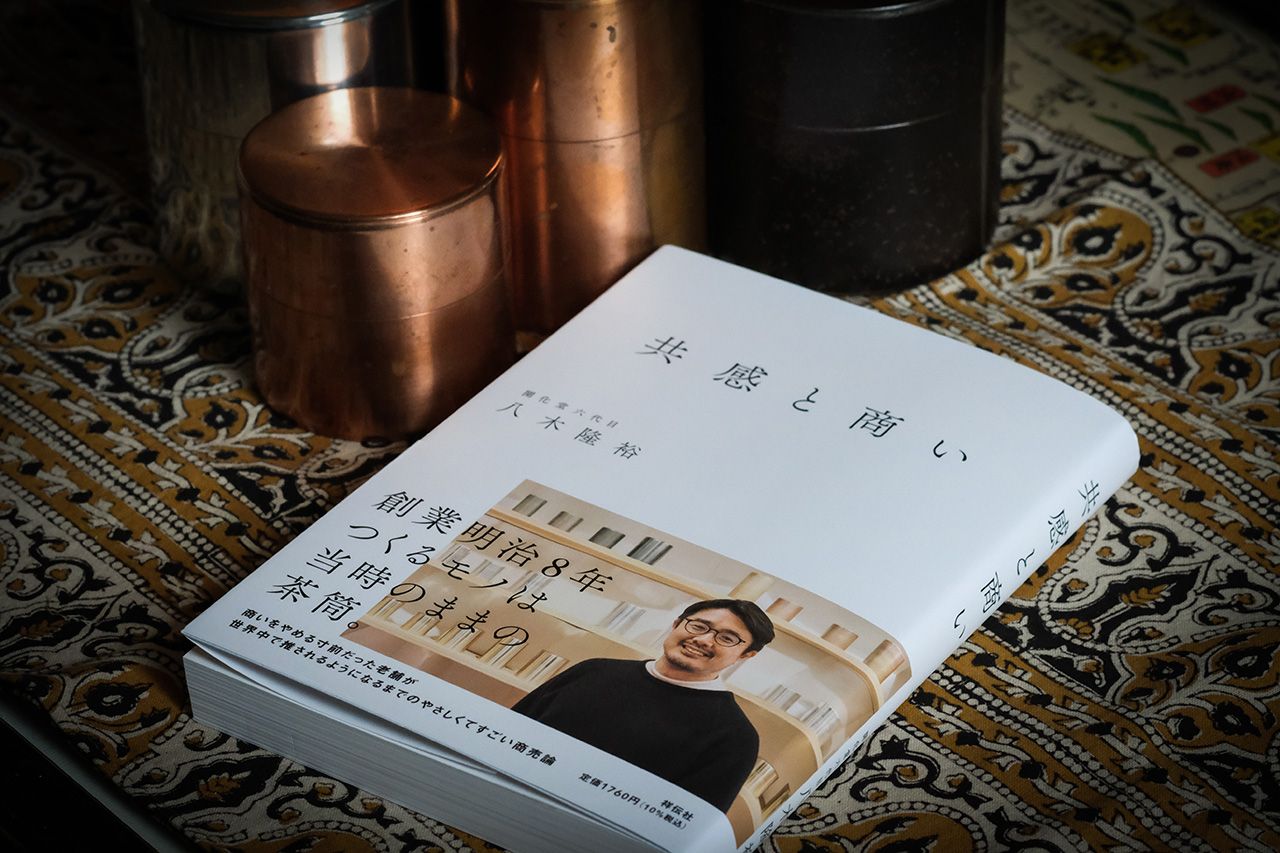

The wide-ranging conversation followed some of the topics covered in Taka’s book, “共感と商い” (“Empathy and Business”), published in March 2023, and this was the first time he was talking about it in English. From the essence of his work to why he vows for an alternative model to extreme consumerism, from experimenting with alternative materials like plastic and carbon fibre to superfans (押し, oshi). We even talked about ChatGPT!

Below I highlight a few of the topics that stood up to me. However, I encourage you to watch the whole conversation (or listen to it during your commute).

Why write a book now

Taka decided to write the book because he felt that following a “big business” playbook, one solely focussed on scale and profit, was not suitable for craft companies. If craftspeople want to double their scale of production they need to double the people working on it. If profit was Kaikado’s only goal, they would have stopped making high quality tea containers that can last for 100 years or more. To this day, they have customers bringing back their tea caddies to be repaired so that they last for another century. What has kept Taka and his forebears going is the feeling of uniqueness of these objects.

Family, small business and feelings

The title of the book is “共感と商い” (Kyōkan to akinai), which I roughly translated as “empathy and business”. However, Taka pointed out that he consciously avoided using the word “business” which in Japanese is written ビジネス using katakana, the syllabary for foreign words. Business is often used for corporations and big companies. Instead he chose 商い, akinai, which has a meaning closer to “small business”.

Taka reflects on how in the beginning, exchanges were human-to-human. Money came later as a practical tool to transact but he feels that in today's way of doing business money comes before human values. That’s why he uses the concept of family throughout the book, to highlight that the first step should be the exchange of feelings, then comes the passing of physical things, and money comes later to allow the trade to happen.

Case in point, when I first met Taka a decade ago at the Salone del Mobile in Milan, he gave me a small copper tea scoop in which he inscribed my name with a chisel. I realise now that throughout the years our mutual exchange has been about feelings, not money (even if I’m a customer of Kaikado and have purchased several tea caddies and spent time at the Kaikado Cafe in Kyoto). Today we consider each other friends.

“In the book I talk about family, of thinking of the world as a family. If I do so, then I don't have to take all the profits for myself, you know, we can share it with all the family [members] in the world.”

Thinking beyond your own lifetime

Thinking and acting long term is embedded in the work of Kaikado and many other Japanese craftspeople. For example, after WWII Taka’s grandfather saw that the market was being inundated by foreign machine-made tea caddies. At the time the perception was that machine-made was the future while handmade was old-fashioned. If his grandfather had put profit first, he would have gone into machine-made tea caddies and eventually these skills would have disappeared from Japan.

“My grandfather thought about the future and the uniqueness of handmade [things] and also I think he was proud of making good quality products by hand. That’s why he never got into machine made tea containers. That’s why we can exist right now. Whenever I have to make an important decision I think about my grandfather and I think about my children and grandchildren. And then I try to think about what we should do right now.”

The essence of the work

What is the essence of Kaikado? “The tea container itself is not the strong point of Kaikado. I think it’s the feeling [you get] when opening the tea container. If when you open the tea container you have a good feeling and when you have tea it has a good taste, that means that the container performed its function of keeping the tea fresh correctly. That is the core value for the tea container and for Kaikado.”

Creating that feeling is the core value of Kaikado and it's the one thing they don’t want to change. All the rest can be adapted to the current era.

“I make other objects so that I can continue making tea containers for the next hundred years.”

Thinking in ecosystems

Different crafts can act as a mirror to each other. In the world of tea, the tea container cannot exist in isolation. You need other tools like the strainer, the tea bowl, the scoop, the kettle and more.

“I think that everything that we bring into this world doesn't happen in isolation, right? And understanding what is your contribution to that ecosystem is important because, even ourselves, we cannot live our lives alone. You know, even if you focus on your own things you require everything that's around you to live, to thrive. What you do has an impact on others and it can be good and it can be bad. I think that's something that often we forget in the business world where it's all about, you know, benefit for ourselves as quickly as possible without realising that the benefits are connected to other things and have consequences.”

The personality of objects

If people can continue using an object instead of disposing of it immediately, that could be part of the solution to the environmental crises. “If you continue using [that object] you can also find out a thing’s 者柄 (monogara), the personality or character of that thing.”

Kaikado’s tea caddies age beautifully through use in a way akin to how one’s personality changes and evolves throughout life. “We often say that the wisdom of the present is based on our failures or mistakes of the past, and we need that period of growth and evolution, and why shouldn't our products follow us in that same sense?”

Changing/Not changing

In 2025 Kaikado will celebrate its 150th anniversary. Taka imagines the company-family’s history as a line made of 150 tea caddies. To help make this line longer one by one, they’ve been taking small jumps, like a portable speaker created for Panasonic or a coffee container. The small jumps are like adjusting to the current era. “But before making a new jump I look at this line of past tea containers. The products we create are an extension of ourselves, are an extension of our society, are an extension of our body.”

Collective imagination and sustainability

Taka and a group of local craftspeople have opened an exhibition at the Kyoto Kyocera Museum where they imagine the future of Kyoto in 100 years. The show has the goal of stimulating the collective social imagination. The starting point is seeing Kyoto as a crafts city with a craft-mind, populated by spaces where things can be fixed so that they are used again and again.

Fixing and repairing for continuous use offers a different lens to look at the price that these objects sell for. If you can use it ten-times longer, or even pass it onto those that come after you, then the price is not high even when compared to cheap, disposable items.

“We created a workshop for fixing and adjusting, rejuvenating the things we have so they can last for 100 more years. [...] If things are not made to be disposable, we can make smaller amounts of them. This can also be part of the solution to the environmental crisis.”

Lived experience is more than words

The Kaikado Cafe was created as a place for the customers to experience the brand naturally without the need to know about the narrative behind what the company does. This learning by experience, not by words, is similar to how Taka learned his craft from his father, not by oral teaching but by doing.

“My father never taught me. He just asked me to watch and learn. So we always pass our philosophy [to the next generation] by hand-to-hand, not by words. It takes a long time, but once you experience it you never forget.”

PS: If you’re left wanting to know more about Kaikado and their philosophy, check out this other conversation we had in December 2020.