Bamboo, Blades and YouTube

During the summer of 2025 I gave myself the task to learn to carve chashaku as part of my embodied research of Japanese crafts. If that sounds too esoteric, let me clarify.

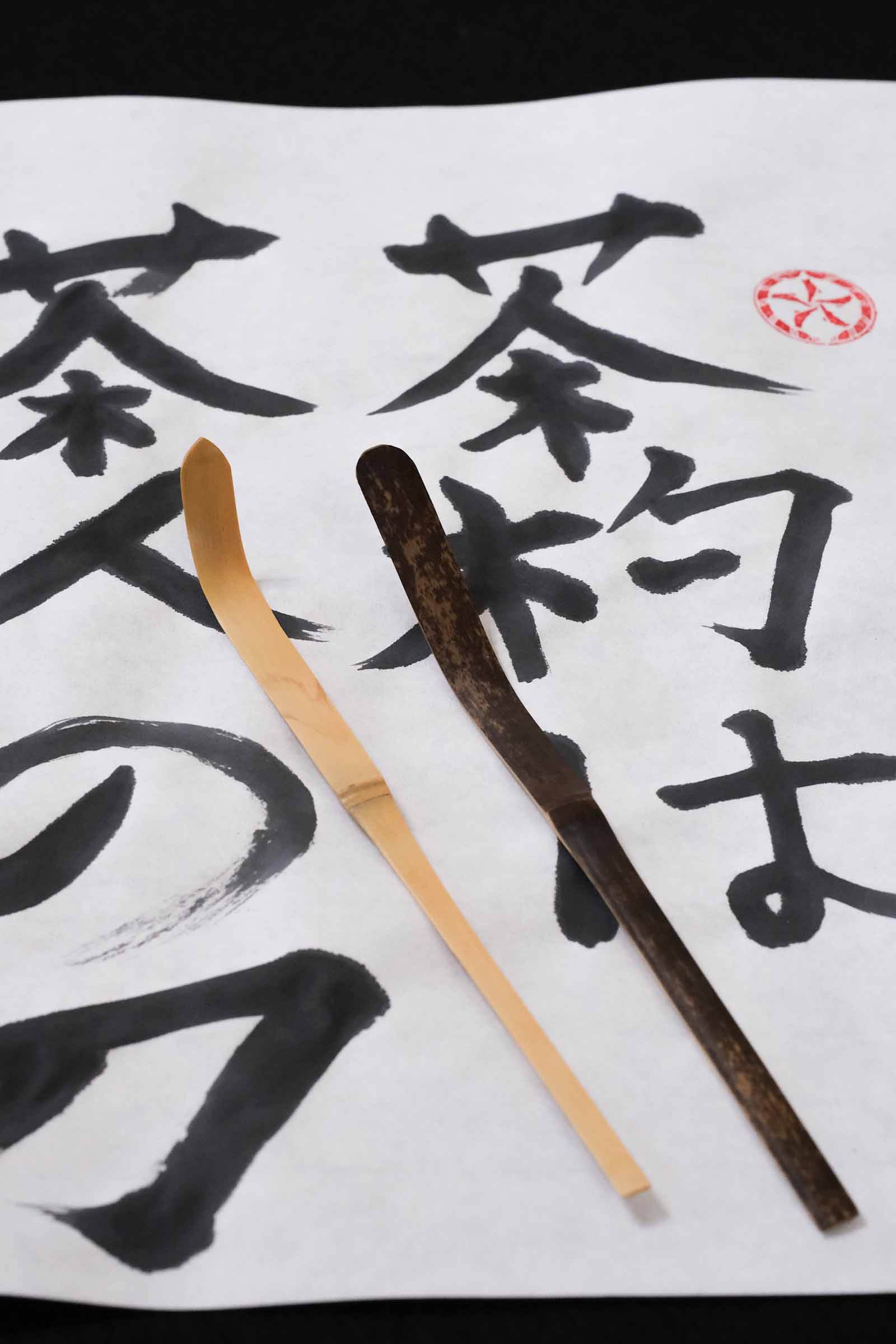

Chashaku (茶杓) are the small bamboo tea scoops used in the Japanese tea ceremony to transfer matcha from tea caddy to bowl. Originally ivory spoons for medicine in ancient China, they're now considered one of the most important utensils in the tea room because they touch the powdered tea directly. A chajin (茶人, tea person) makes their own chashaku as a sign of commitment to Chadō, the Way of Tea.

茶杓は茶人の刀

"The chashaku is a tea person's sword"

— Japanese saying

I decided on making chashaku in part because I love tea and the web of arts and crafts connected to tea culture like pottery, calligraphy, flower arrangement, incense and tea room architecture. But also because it requires very little equipment. Besides, it allows me to spend time creating away from screens, which already occupy a big part of my day.

Digital Sensei

The first step was to go to the biggest repository of knowledge that humans have ever created: YouTube. There I found many tutorials, some more didactic than others. My Japanese isn't strong enough to follow everything but, in keeping with the learning approach of a shokunin, I watched carefully to pick up subtle hand gestures and sounds. [Playlist with my favourite chashaku making videos].

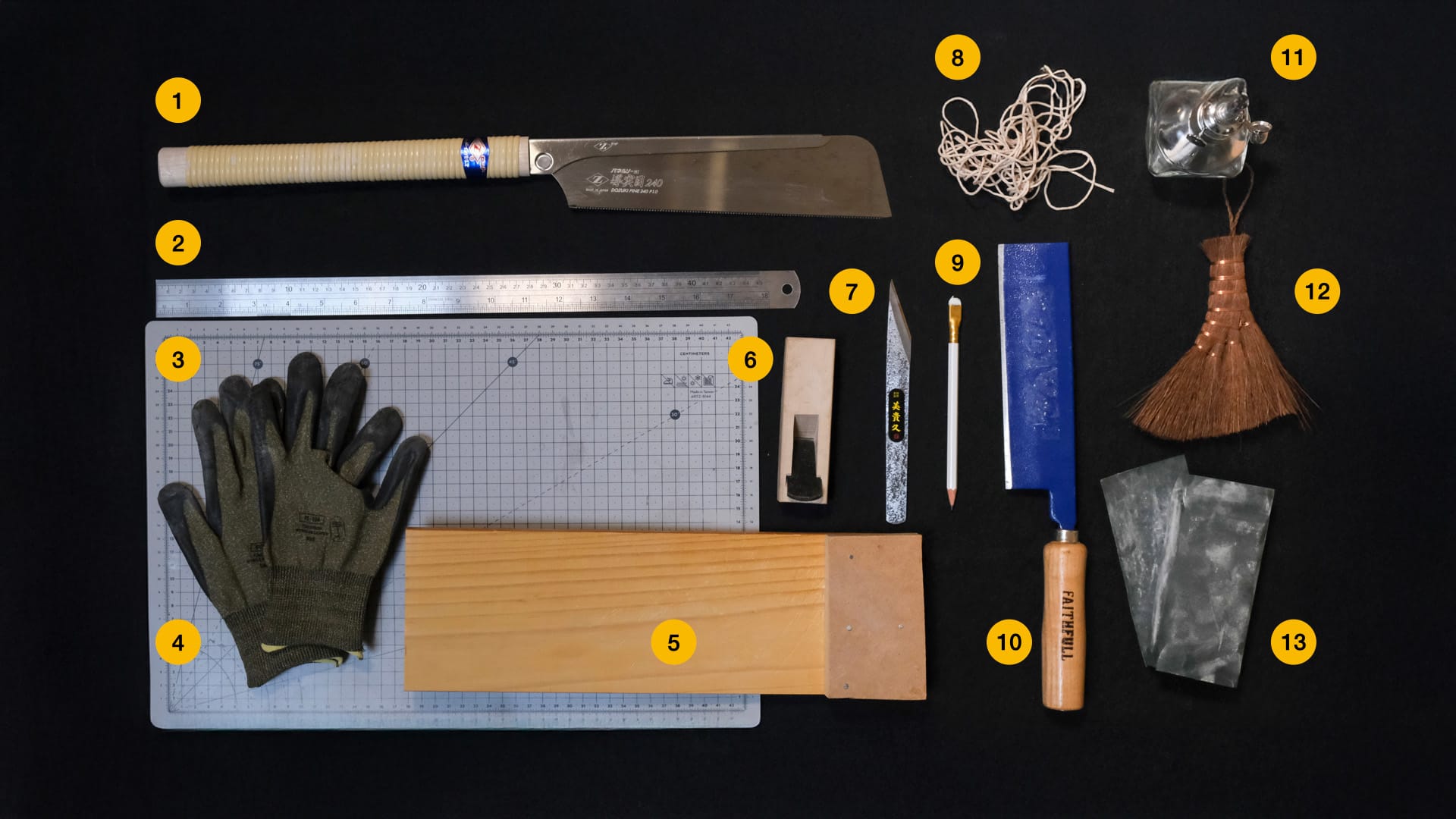

Once I had a rough sense of the process, I bought the materials and tools. At the bare minimum, you need a few lengths of dry bamboo (I bought an assorted bundle for DIY projects) and a carving knife, called kiridashi (切り出し, cutting out) or kogatana (小刀, small blade).

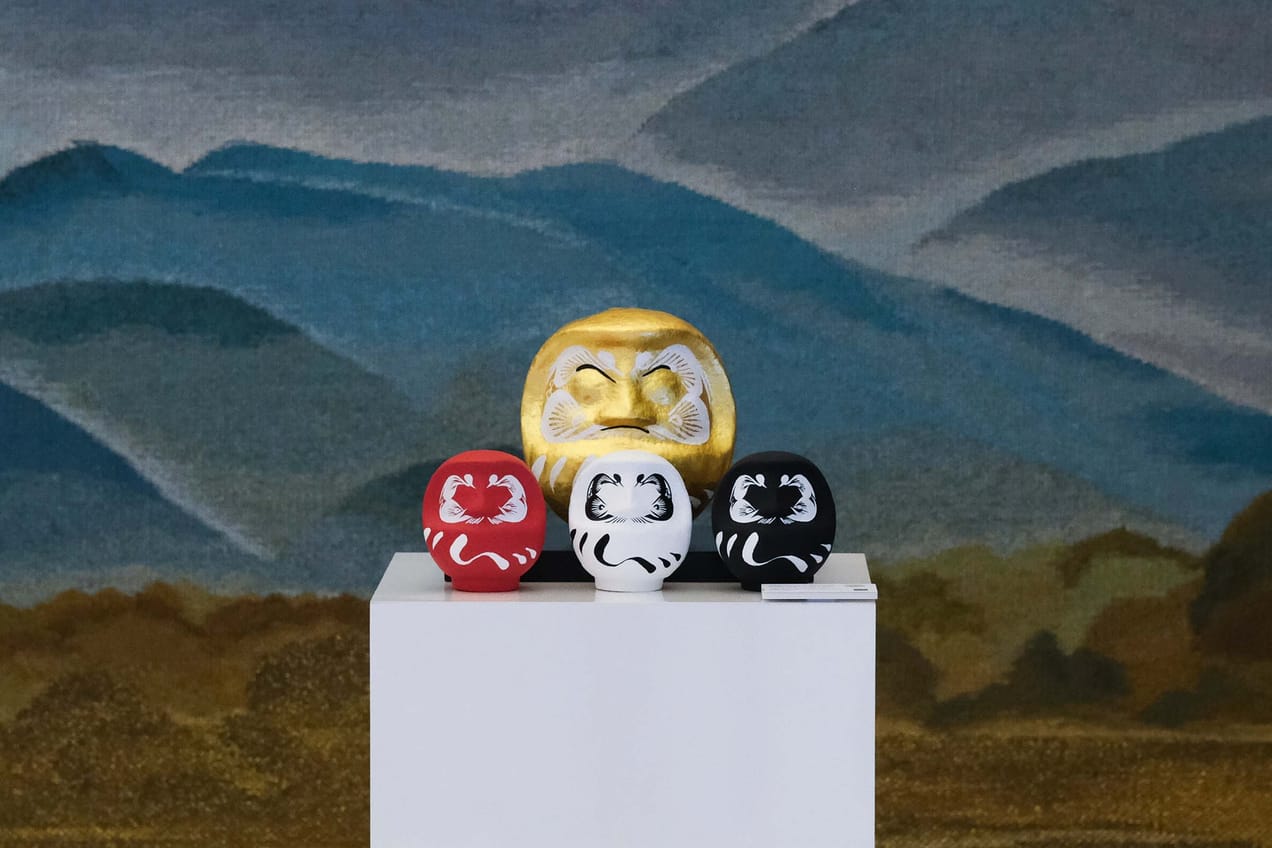

Mapping the process. Photos by Gianfranco Chicco

The kiridashi has a single-bevel blade, a flat back and an angled cutting edge. I got mine as a gift from James of Cutting Edge Knives, a UK online shop specialised in handmade Japanese knives (and accessories, not Kill Bill katanas) with the promise that I would share my learning process (thank you James!).

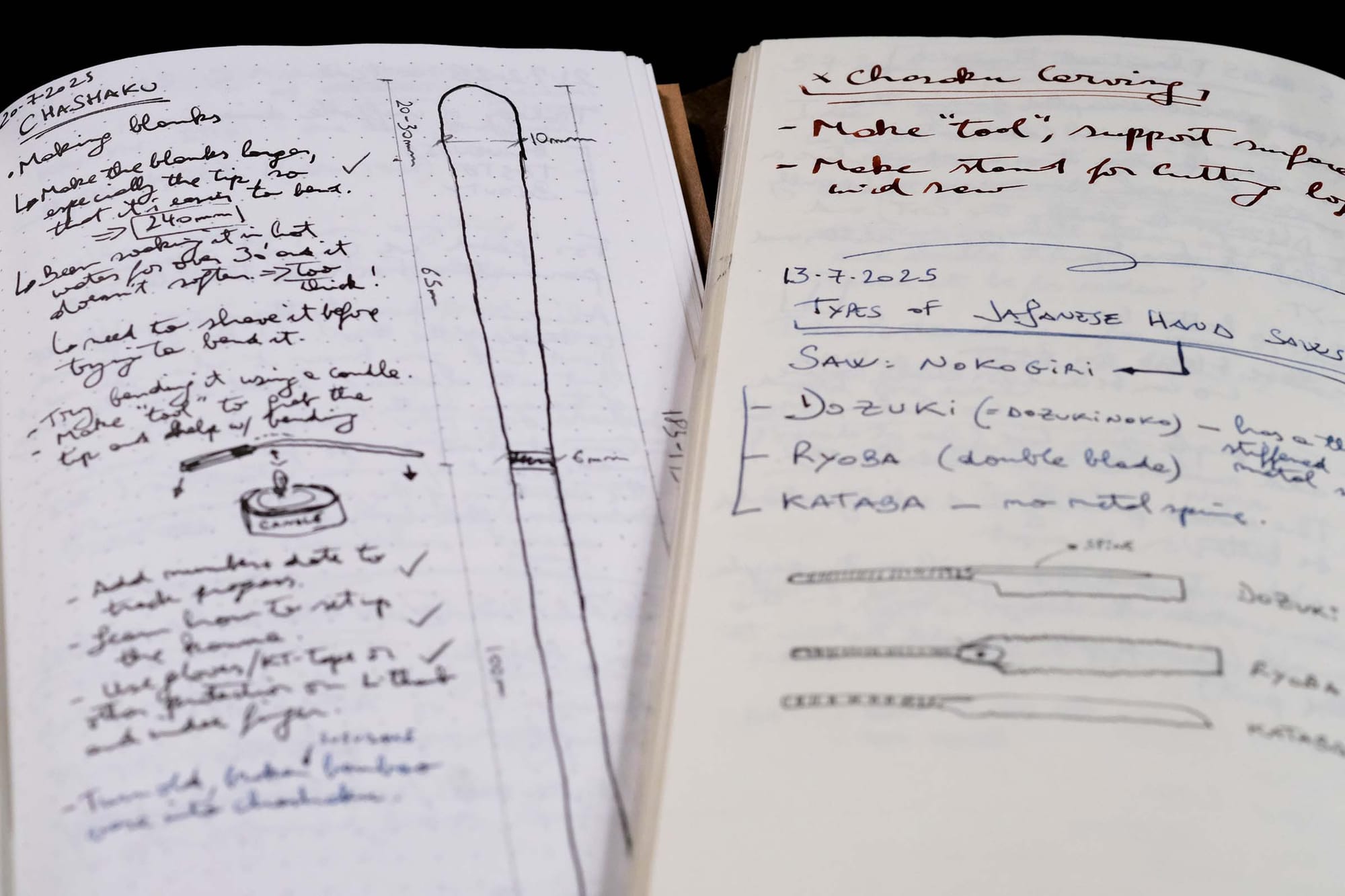

My first attempt was unambitious. I just wanted to get to know the tools, which other than the kiridashi included a dozuki saw, a small log splitter and 200-400 grit sandpaper. I made a handful of blanks out of black bamboo and quickly realised they should have been longer. My first fully finished scoop, the '001', was too thin but decent enough to be useful.

Geeking out on tools

Next I became infatuated with Japanese wood planes, which are not strictly necessary for making chashaku but in the past were used in lieu of sandpaper. I bought a small sori kanna, or compass plane, which has a convex bottom that's handy for smoothing the chashaku's length.

One thing common to many Japanese hand tools is that they're often sold unfinished, requiring the user to personalise them to their own style of making. A blade needs sharpening and, in the case of the kanna, the wooden holder has to be "tuned" for it to cut properly. I went back to YouTube but hours of watching left me none the wiser. I turned to another digital platform in search of a solution: Instagram.

I posted a story asking for help and promptly received a comment from Frederick Dodson, someone outside my network. He’s a British craftsman working in the Japanese tradition of hand-tool carpentry who, serendipitously, was taking part in an exhibition not far away from my home. When we met, he showed me how to safely use a fine chisel and a hammer to carve out bits of the kanna’s wooden base to obtain the right fit for the blade (note to self: add Japanese hammers and chisels to my wishlist). Frederick was extremely kind with his time and expertise and proof that there’s still some “social” left in social media.

Six Scoops, Six Lessons

I set up a mobile workstation in the living room, with a cutting mat on the coffee table and the tools laid out on the floor for easy access while sitting on the sofa.

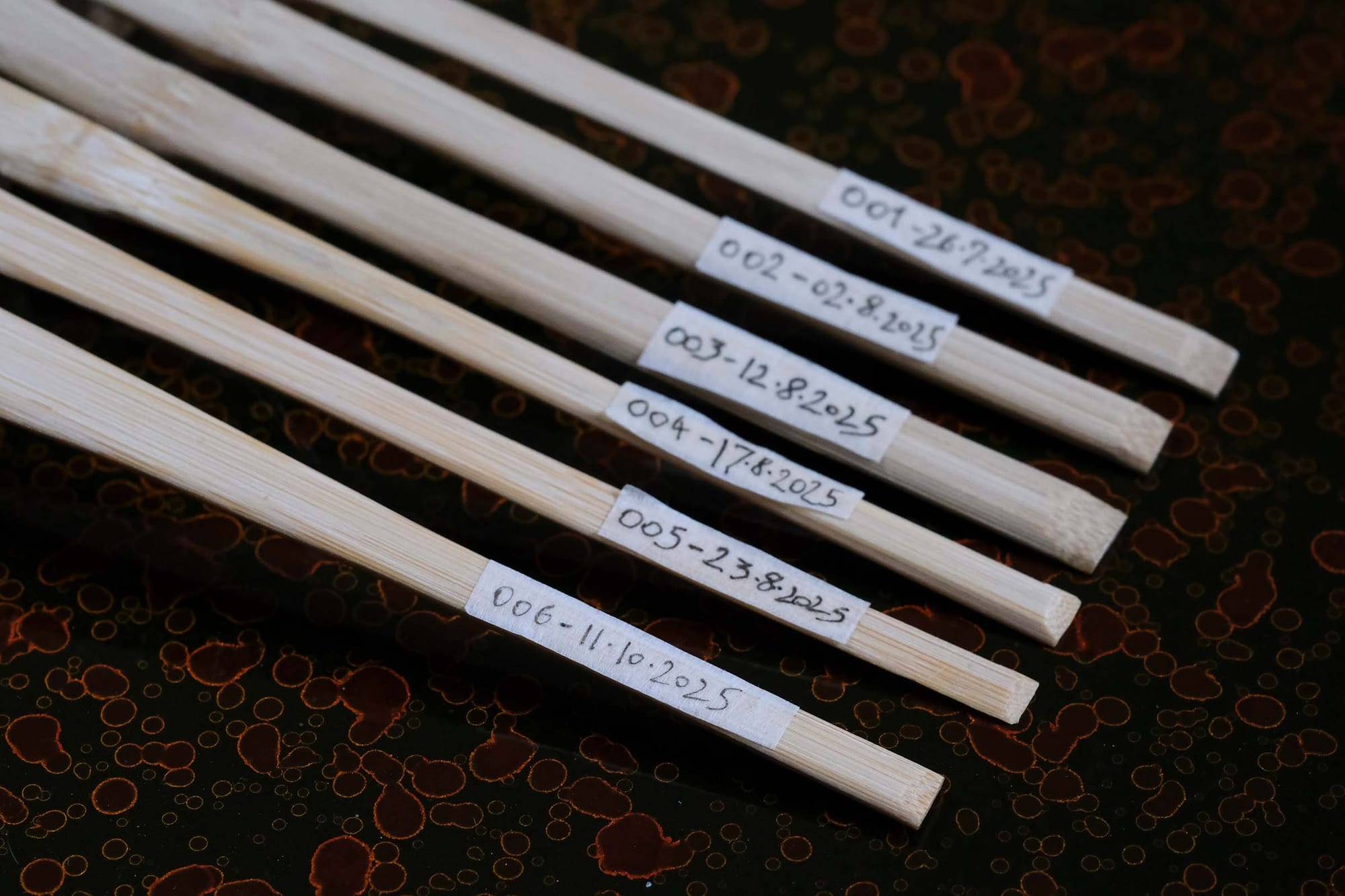

So far I've made half a dozen chashaku and have blanks ready for six more. I've been using them for daily tea practice instead of the established makers' ones I own. Feeling their imperfect forms and uneven proportions offers further feedback that shapes the next scoop.

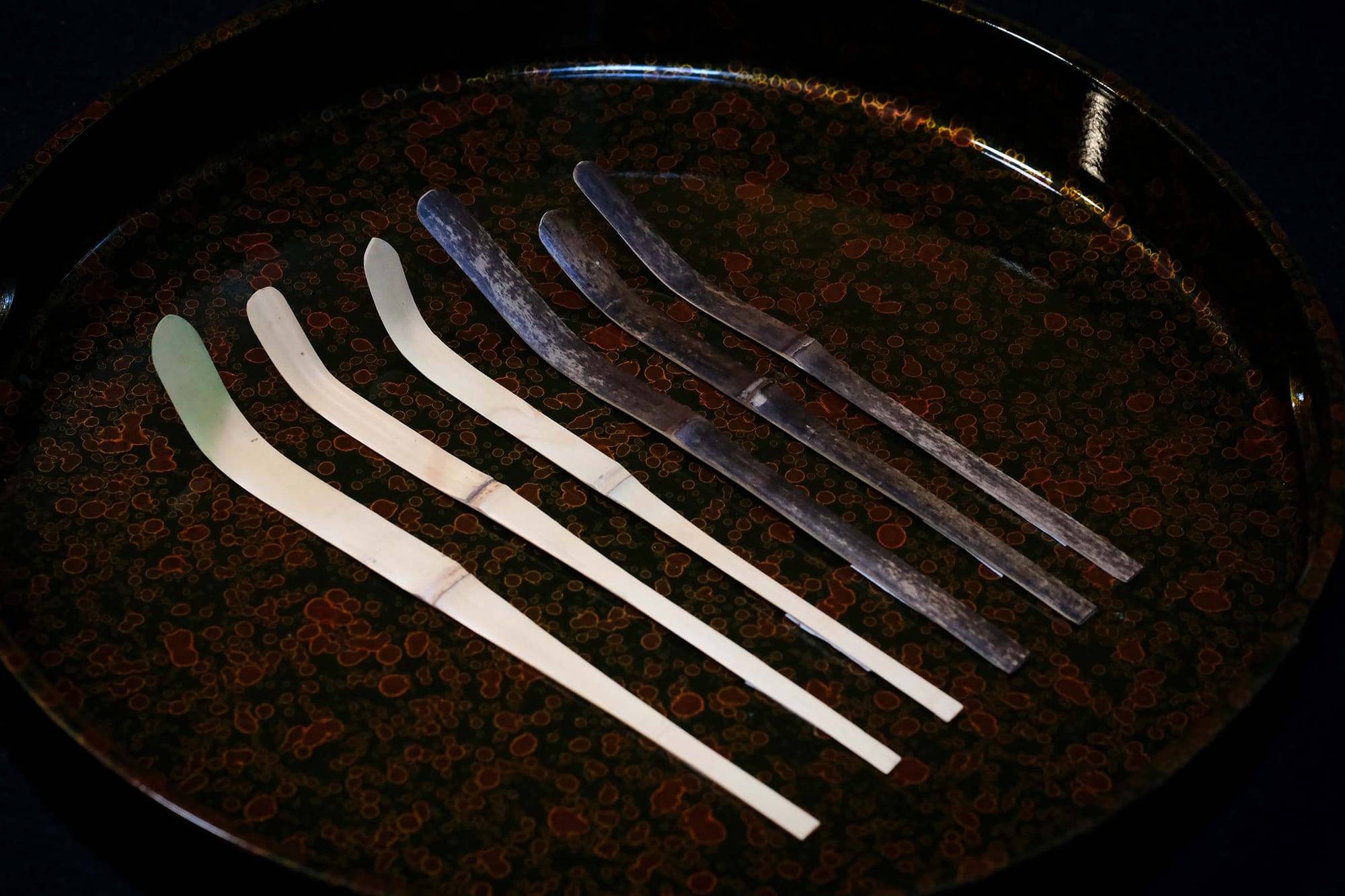

The first two taught me how to prepare the material and use the tools. Later iterations focused on refinement: adjusting the tip shape and node position, balancing the handle so it rests properly atop a tea caddy, imitating styles preferred by different tea masters.

First six chashaku. Photos by Gianfranco Chicco

My knowledge of making is slowly moving from brain to hand, from intellectual into tacit. Each chashaku develops my understanding of the medium... and of my limitations. Every time I rewatch the videos and look at reference books, I notice details I couldn't see before. Maybe I'll close the gap after making fifty or a hundred more scoops. Eventually I'll seek out a workshop with one of the master craftspeople in Takayama, a village in Nara Prefecture famous for bamboo crafts for tea for over 500 years.

What lies ahead is getting hold of better quality bamboo (which would have been wasted on my early attempts), making the tsutsu (the tube that protects the chashaku), and other tea items like hanaire (flower vases) and kashi-kiri (little picks for cutting sweets). Am I being too ambitious? Perhaps. But I've always learnt best and had the most fun by doing rather than studying.

Like the content of The Craftsman? Share it with a friend! You can support my work by offering me a virtual coffee ☕️

つづく