Talking by making: soba noodles in Tokyo

Akila Inouye runs the Tsukiji Soba Academy in Tokyo. A fan of molecular cuisine, his teaching method relies on getting to know the history of soba, grasping the underlying chemistry of its preparation and of course cooking and eating them in different ways.

In November 2023 I embarked on a research trip to Japan for my book on what we could learn from Japanese craftspeople, shokunin, to improve how we live and how we work.

The COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns had limited my means of exploration to doing online interviews, which gave me the opportunity to talk with extraordinary makers about their work and lifestyle. The video series The Essence of the Shokunin was the result of some of these conversations.

However, when it comes to doing a deep dive into craftsmanship, especially from a culture as different to my own as the Japanese one, the reach of words is extremely limited. Tacit knowledge and mastery are almost impossible to transmit with words alone. The way forward was to acquire knowledge through direct experience, to talk by making.

Other than visiting workshops in different towns, I decided on two specific activities to get my hands dirty with: soba (buckwheat noodles) and pottery. What follows is the first in a multi-part series regarding my craft travel adventures.

Making Noodles at the Tsukiji Soba Academy

Soba noodles became a staple of Japanese cuisine in Edo, old Tokyo, during the days of the Tokugawa shogunate between 1603 and 1868. In the 1800s it turned into a popular snack accessible to all, with ubiquitous pop-up market stalls and deliveries handled by vigorous joggers and later bike riders too (in the 1960’s deliveries by bicycle were banned due to the increasing number of accidents involving cars). While the most traditional soba are made with 100% buckwheat, more often than not they have a 2:8 ratio of wheat to buckwheat. Soba can be enjoyed hot or cold depending on the season. My favourite way is as zaru-soba, cold noodles accompanied by a dipping sauce - tsuyu - made with soy sauce, mirin, sugar and dashi.

Following the recommendation of my friend Nobi, I signed up for a class with renowned soba specialist Akila Inouye. Akila sensei runs the Tsukiji Soba Academy in Tokyo. A fan of molecular cuisine, his teaching method relies on getting to know the history of soba, grasping the underlying chemistry of its preparation and of course cooking and eating them in different ways.

The Tsukiji Soba Academy was set up in 2002 and in the early 2000’s, Apple’s Steve Jobs sent his private chef to train in soba-making with Akila sensei. Soon after, Apple started offering soba to its employees at the Caffè Macs (allegedly you could order noodles topped with sashimi, something you’ll never see in Japan).

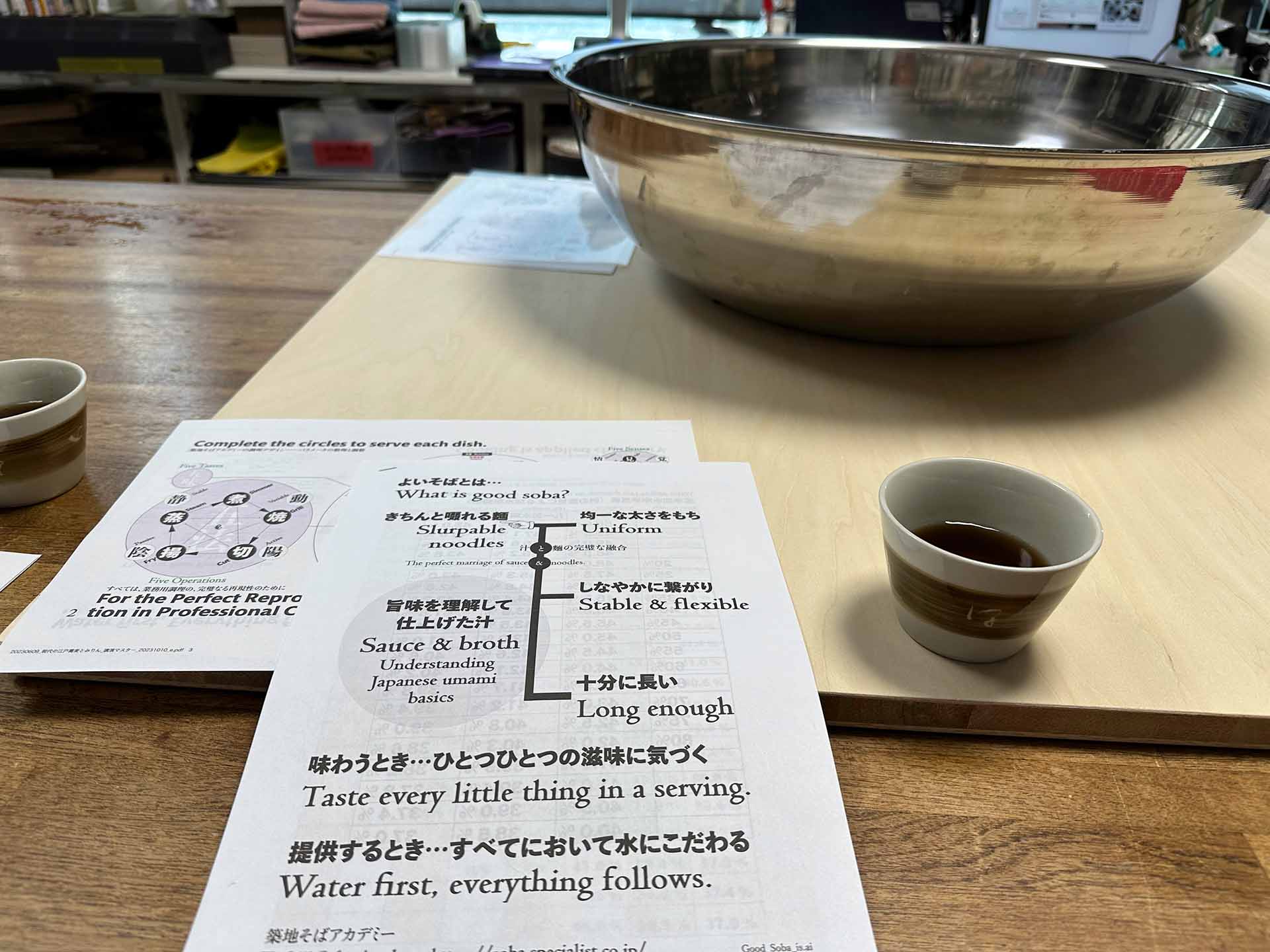

Akila is as much of a rigorous scientist as he is an artist. We started by studying what defines great soba which, no pun intended, boils down to producing slurpable noodles that are uniform, stable, flexible and long enough, and marrying them with, as he puts it, “an awesome sauce”.

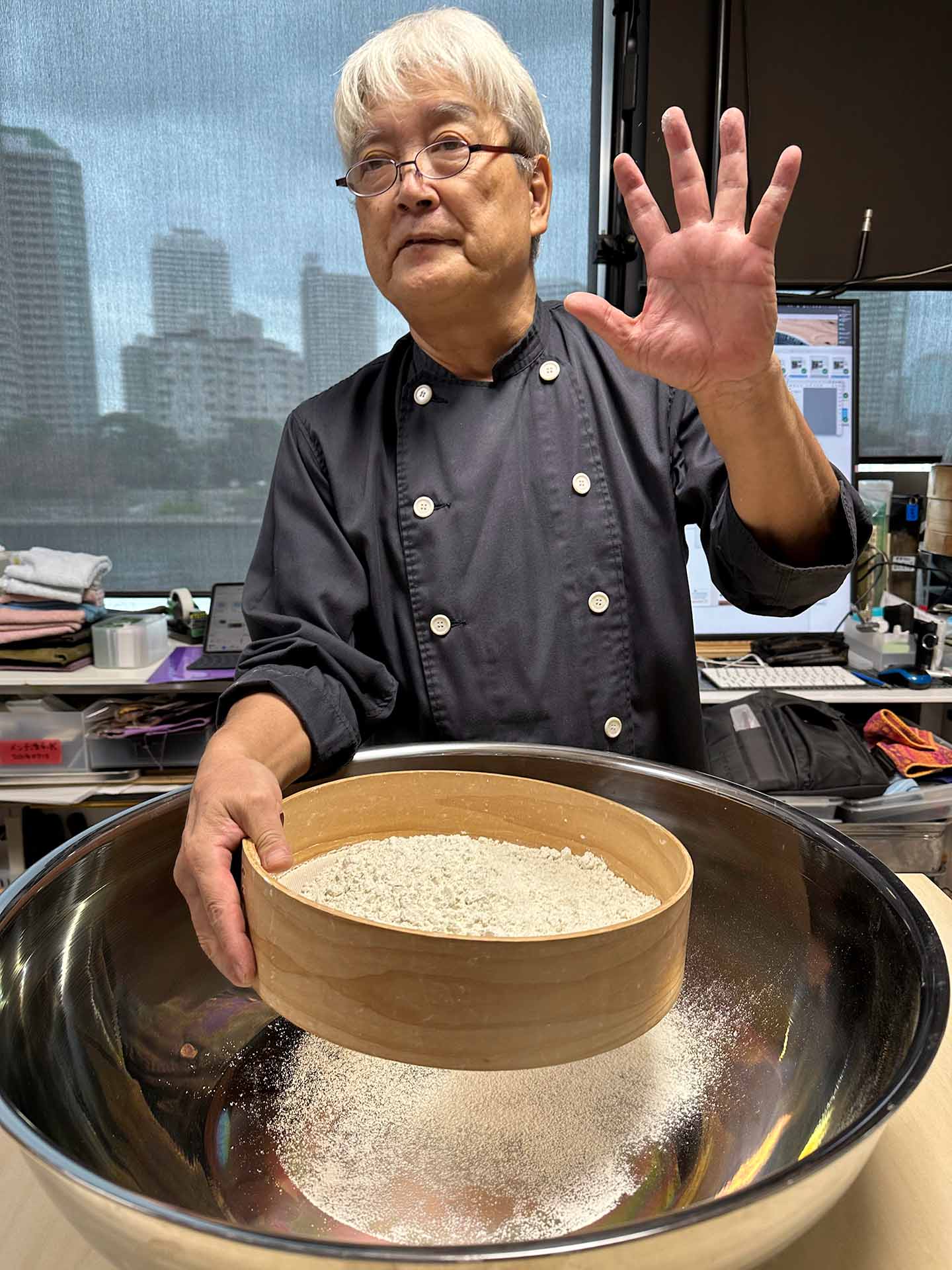

Making soba is as much art as it is science. Akila sensei would make sure the measurements of every single ingredient were just right.

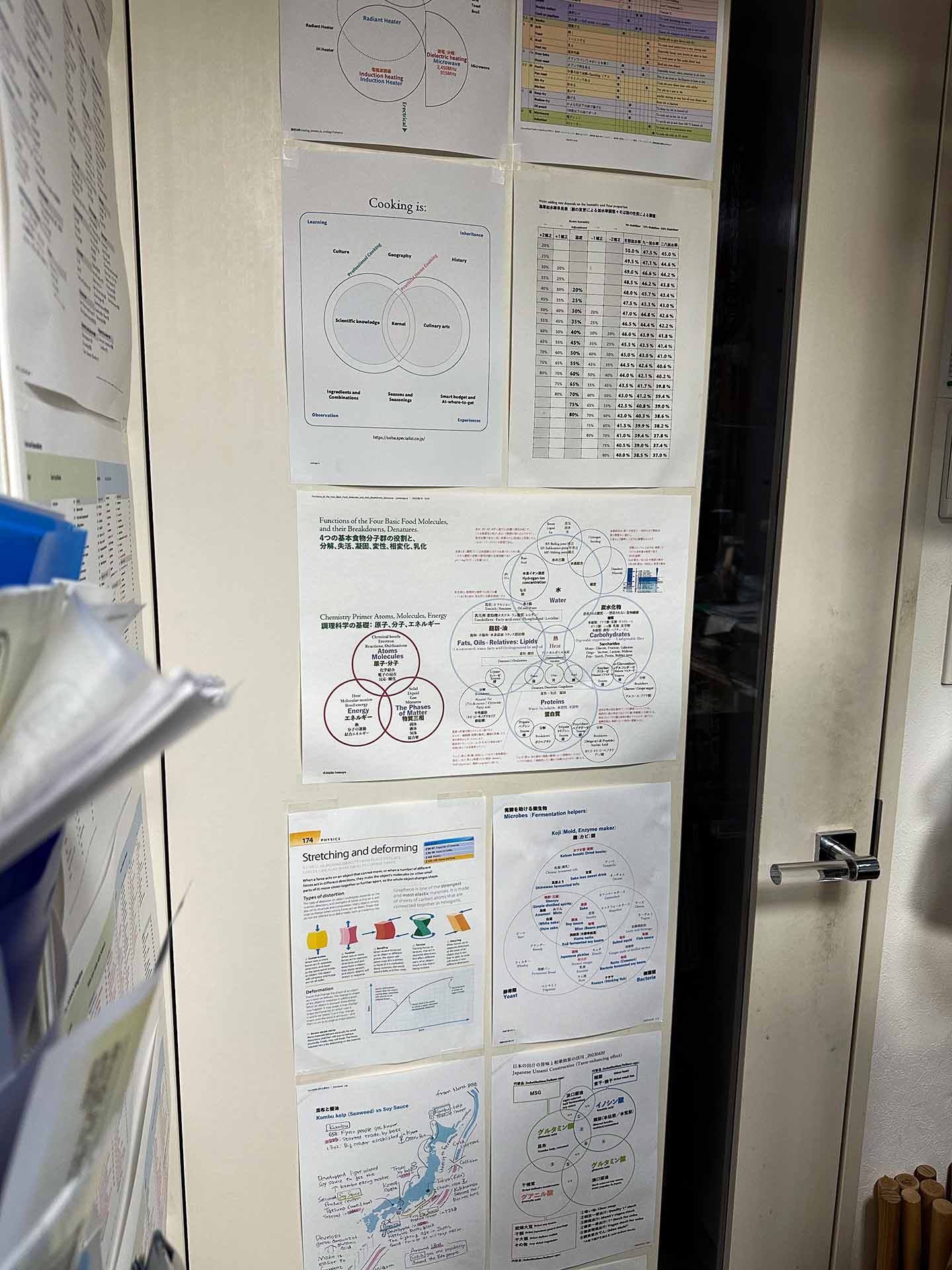

The academy’s studio overlooks the Sumida river close to what used to be the Tsukiji Food Market. The space is compact, full of books and any imaginable cooking utensil arranged in a delicate equilibrium. On the walls, printed aphorisms like “Water first, everything follows” and “Less is more” reminded me of a design studio rather than a kitchen, but the chef stands by those as key tenets of his cooking style.

The reason why I had chosen soba was because I’m already experienced at preparing Italian-style pasta, although I would later discover that soba is much more complex. The ingredients are easy to find at any well stocked Asian grocery store. The soba kiri, a specialist knife, might be the only specialty tool involved, but you could still manage with what you have in your kitchen.

The soba-kiri is a special knife used for cutting the noodles. The one picture here was co-designed by Akila Inouye.

Making good soba requires understanding the culinary principles involved and a solid technique. Above all, it relies on your mind and five senses working in unison. Akin to other crafts like woodturning or ceramics, the quality and provenance of the source materials is of utmost importance.

During five hours we (me and two friends) put our hands to work during key parts of the process like mixing, kneading and cutting the dough and cooking. The result of our effort would be evident straight away… and it was really tasty!

The final step is to cook and taste your own creation.

Before embarking on this trip I half-joked with friends that one day I will open a soba yatai, a mobile food stall, under a bridge in London. The city has plenty of decent udon and ramen shops but no soba that I know of. Because this was a participatory demonstration rather than a fully fledged professional course, I didn’t learn enough to handle the whole process from beginning to end by myself. But the good news is that Akila also runs a professional course over ten to twenty consecutive days and I’m considering a prompt return to Tokyo to carry on with my training. My dream of becoming a soba cook might not be that far away after all.

Making soba is serious business!

つづく